Josiah Quincy was a lawyer, politician and abolitionist. As a lawyer, he rarely practiced. As a politician, he was largely disregarded, except for his time as "The Great Mayor" of Boston. As an abolitionist, he wrote papers on the subject and supported his abolitionist son Edmund. He is most famous in his hometown of Boston where his policies changed the face of the burgeoning city. Even today, nearly 200 years after his death, his contributions are a part of rich history of the city.

Josiah Quincy (not to be confused with the many other Josiah Quincys in his family) was born in Boston, Massachusetts on February 4, 1772. He was the son of Josiah Quincy Jr. and Abigail Quincy nee Phillips. Both of his parents came from wealthy and influential families. The Quincy family was full of politicians, teachers and military (militia) men. His father was a well-known patriot who aided John Adams in the defense of the British soldiers involved in the "Boston Massacre."

When he was in his early thirties, Josiah Quincy Jr. died of tuberculosis. His son was just a toddler at the time, but he was left in the capable hands of Abigail and his grandfather–Josiah Quincy. He began attending the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts when he was six years old. Even there, he was under the influence of his family. His uncle, Reverend Samuel Phillips, was his teacher. From there, he went on to study at Harvard University like most great men in Boston at the time. He graduated from Harvard in 1793, but that was not the last he would see of the revered school.

After graduation, Josiah Quincy began his apprenticeship in law. He became a lawyer, but decided to spend his life in politics. Two years after his graduation from Harvard, Josiah Quincy was elected to the Boston Town Committee. (He was a Federalist.) He remained in that position for five years before running for Congress. He was not successful his first time around. However, he was elected in 1804, and he left for Washington, D.C.

While Josiah Quincy was a member of the Boston Town Committee, he married Eliza Susan Morton. The couple would go on to have seven children together, notably Edmund Quincy and Josiah Quincy Jr. Edmund would go on to become a famous abolitionist periodical editor. Josiah Quincy Jr. would follow in his father's footsteps and become Mayor of Boston.

Things did not turn out well for Josiah Quincy in Washington. His ideas were becoming passé and his time in Congress was not noteworthy, except for his departure. In 1813, Josiah Quincy disagreed with the United States' latest war with England, so he returned home to Boston, where he was elected to the Massachusetts State Senate. He spent 12 years in that position. He was also a delegate to the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention in 1820 and a Massachusetts House of Representatives Judge in 1821. In 1823, Josiah Quincy was elected Mayor of Boston.

Josiah Quincy made Boston a cleaner, safer place to live. He focused on juvenile delinquent reform. He brought municipal water and sewage to the city. He organized the fire department and more. Most notably, he cleaned up the area where Quincy Market is today and established the market, which still stands facing Faneuil Hall. In a modern city, it is a rather awkward position for the building, but it makes for great historical atmosphere and street performer fun. Mr. Quincy probably never imagined Quincy Market as it is today, but he would surely be pleased to see how beloved it is by the city's residents.

Josiah Quincy served as Mayor of Boston for five years. On June 15, 1829, he became President of Harvard University. Despite his best efforts, his time there was marked with unrest in the student body. There were violent protests and the students openly disliked Josiah. Quincy did his best to punish the students responsible and put his efforts toward making the school better. He did make some great changes to the school, but he never did win over the students. He retired from his post on August 27, 1848.

In Josiah Quincy's twilight years, he wrote a great deal about the history of some famous Boston institutions. He also wrote about his son Edmund's passion–abolitionism. He died on July 1, 1864 and was interred at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Historic Biographies

Tuesday, January 2, 2018

Tuesday, September 5, 2017

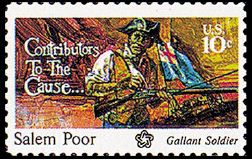

Salem Poor: A Revolutionary War Hero Born a Slave

|

| 1975 U.S. Postal Stamp |

Salem Poor's early life was presumably that of any slave born into servitude, but he somehow managed to buy his freedom in 1769. The price he paid for his freedom was 27 pounds. Soon after Poor became a free man, he married another free African-American. Her name was Nancy, and the couple had a son together.

In 1775, war broke out against the British. Salem Poor joined Colonel Frye's Regiment, leaving his wife and son to fight for the colonies. On June 17, 1775, he appeared with his regiment on Breed's Hill to build fortifications against the British. That day, he fought in the battle that would become known as the "Battle of Bunker Hill."

A document exists in the Massachusetts State Archives that describes Salem Poor as a "brave and gallant soldier." It also states that, on June 17, 1775, he "behaved like an Experienced officer, as well as an Excellent Soldier." [sic] It went on to say "to set forth the particulars of his conduct would be tedious." The document is dated December 5, 1775. No less than fourteen officers who witnessed Salem's deeds that day signed it.

The particulars of Salem Poor's service at the Battle of Bunker Hill are not known. However, one can assume that he went beyond what was expected of him to be spoken of in such a way by so many officers, one of whom was Colonel William Prescott. No other man who fought on Breed's Hill that day was honored in such a way. Salem went on to fight at the Battles of Valley Forge, Saratoga, White Plains and Monmouth. His deeds in these battles are unknown as well, but we can imagine that he was no bystander.

Salem Poor appears to have gone back to the life of a barely regarded African-American man in Massachusetts after the war. Despite his gallantry and the sacrifices he made for his country (leaving his family and fighting in a war that hardly benefited him), his life after the war has seemingly gone undocumented.

Monday, May 29, 2017

Dwight Hal Johnson: Medal of Honor Recipient

|

| U.S. Army Medal of Honor |

Dwight Johnson was born in Detroit, Michigan on May 7, 1947. He was drafted during the Vietnam War and went on to earn the rank of Specialist 5th Class. He was a tank driver. In this capacity, he found himself in a conflict with a North Vietnamese force on January 15, 1968. He was 20 years old.

That day in the Kontum Province in Vietnam, Dwight Johnson was "a member of a reaction force moving to aid other elements of his platoon, which was in heavy contact with a battalion size North Vietnamese force." according to the official report. As soon as Dwight arrived, one of the tracks on his tank broke. He was a sitting duck, or at least his tank was; Dwight was not the sort of man to sit there. He took the only mobile weapon within his reach–a .45 caliber handgun–and exited the tank. He immediately went directly for the enemy. He used up his ammo dispatching several members of the opposing force, miraculously remaining unharmed.

When Dwight Johnson ran out of ammo for his .45, he went back to his tank, which was naturally the focus of much enemy fire. Against the odds, he managed to get in, get a sub-machine gun and get out without being killed. He went straight back into the midst of the enemy and killed a few more. He continued his attack until he ran out of ammunition once again. At this time, Dwight Johnson went to a different tank and saved a man's life.

Dwight Johnson's platoon sergeant had an injured man in his tank. Dwight, now unarmed, went to the tank and pulled his fellow soldier out. He then carried him to a personnel carrier. Johnson then returned to his platoon sergeant and helped him fire the tank's main gun until it jammed. Never one to stop when the odds were against him, Johnson returned to his tank one last time. There, he operated the tank's .50 caliber machine gun until the conflict was over. He was exposed the entire time.

This conflict lasted roughly half an hour. In that time, Johnson killed anywhere between 5 and 20 enemy soldiers. Unfortunately, this seems to have broken the man. After going home and receiving the highest award any member of the military can receive, he became unhappy. Doctors said that he suffered from nightmares, depression and survivor's guilt. Modern medicine tells us that he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Sources say that when Dwight Johnson came home, he buried himself in debt, despite getting a job as a recruiter. He was also severely depressed, despite having a wife and a baby boy. Accounts of what happened as a result of this are conflicted.

Some say that Dwight walked in on an armed robbery at a liquor store and was shot. Many more sources say that Dwight was the man doing the robbing, but that he did not fire a single shot. Either way, he was shot to death by a liquor store clerk on April 30, 1971 in Detroit, Michigan. He was only 23-years-old. Dwight's mother reportedly felt like her son wanted to die, but needed somebody else to do the killing.

Dwight Hal Johnson was a hero, regardless of the manner of his death. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, where he belongs.

Sources

Johnson, Dwight, retrieved 8/31/10, cmohs.org/recipient-detail/3317/johnson-dwight-h.php

Dwight Hal Johnson, retrieved 8/31/10, findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&Grid=5758187

Monday, January 23, 2017

Paul Revere: Patriot and Craftsman

|

| 1813 Gilbert Stuart portrait of Paul Revere |

Paul Revere was born in Boston in December of 1734. He was the son of Paul and Deborah Revere. Paul was one of eight of the couple’s children that survived to adulthood. Paul Sr. was a French immigrant who had come to America to seek his fortune and had become a goldsmith. His father changed his name from Apollos Rivoire to Paul Revere after coming to America. Paul Jr. attended the North Writing School for a few years and then his father took him as an apprentice in his goldsmith business.

In 1754, when Paul was nineteen years old, his father died, leaving him the business and the family to care for. In 1756, Paul Revere volunteered for the Crown Point Expedition. He went to Lake George, New York as an officer to fight the French troops there. The following year, he married Sarah Orne. Together, the couple had a total of eight children, two of which died in infancy.

During this time in Paul Revere’s life, tensions between the colonists and the British troops in Boston were rising. Taxes were increasing greatly and it was putting a strain on Boston’s economy. Paul became a freemason and was introduced into a secret organization called the “Sons of Liberty” by a fellow freemason named Dr. Joseph Warren. Paul Revere became a very active member of the “Sons of Liberty” and he also did what he could to help spread propaganda concerning the British. He began making engravings of political cartoons for publications and when the Boston Massacre occurred in 1770, Paul made his most famous engraving ever.

In May of 1773, Paul’s wife died shortly after giving birth to a daughter; the baby died not long after her mother. That fall, he married Rachel Walker, with whom he would have another eight children, three of which died before the age of four. The marriage took a lot of the strain off of Paul, who had been juggling his covert activities, his job and his children, since the death of his first wife.

In December of 1773, the British tax on tea had the people of Boston furious. When a large shipment of tea came into Boston and was sitting on ships in the Boston Harbor, some of the colonists decided that it would be a good idea to dress as Indians and dump the tea into the ocean. It is unknown if Paul Revere was directly involved in the Boston Tea Party (as the event would come to be called), but it is certain that his political cartoons helped spread animosity for the British among Bostonians. That year, Revere also became a messenger rider for the Committee of Correspondence and the Committee of Safety.

Delivering correspondence and news brought in a little extra money for Paul, which he could’ve used seeing that the British troops had closed off the port in Boston and effectively crippled the economy there. However, he was also helping his cause by delivering news as far as New York and Pennsylvania. He and other messengers like him were a critical line of communication for patriots throughout the colonies. In 1774, Paul took his patriotism to another level and began working with other patriots to spy on the movements of British troops in Boston.

On the night of April 18, 1775, these spies noticed that the some British troops were on the move. Dr. Warren asked Paul Revere to ride out and spread the news. He was also asked to get the message to Samuel Adams and John Hancock in Lexington. It was thought that the British troops meant to arrest them. Contrary to popular belief, Paul Revere was not alone in his mission that night. Two other men were sent on different routes with the same goal and their warnings prompted other men to spread the word as well. Because of these men, the Massachusetts militia and minutemen were able to prepare for the arrival of the British in Lexington and Concord.

In the early morning hours of April 19, 1775, the three original riders met up and were arrested. The other two riders were able to escape, but Paul Revere was detained for a while. He was eventually let go, but his horse was taken. He then traveled on foot to Lexington Green where he witnessed part of the first military engagement of the American Revolution.

After his famed ride and the Battle of Lexington and Concord, Paul Revere continued his printing and participated in the revolution as much as he could. He joined the Massachusetts militia and was eventually made a Lieutenant Colonel. He was given a post as the commander of Castle Island in Boston, but he saw virtually no action until he was sent to Maine with the Penobscot Expedition.

The battle in Penobscot ended disastrously for the Americans, troops and officers alike scattered, while disobeying orders. When the troops returned home, Revere and others were charged with insubordination and cowardice. Revere prided himself in his patriotism and was ashamed of this charge. He requested a court martial and was eventually given one. It was found that in light of the horrible planning and execution of the expedition and the subsequent battle, there was no way orders could have been given or received properly. The men were acquitted of all charges.

In 1785, the fledgling nation officially gained its independence. Paul Revere continued with his goldsmith business in Boston and met with some success, despite the economy, by crafting items that were attainable for average citizens and not just the wealthy. He also branched out and opened a foundry as well as a hardware store. His new businesses were also successful and by 1800 he could afford to branch out yet again and begin rolling copper. Once again, he met with success. In fact, his copper was used in the building of the USS Constitution, and the New State House.

In 1801 Paul built a second house for him and his wife in Canton, MA. Paul seems to have been happy at that home and even wrote a poem about living there. He continued being involved with his companies into his old age and spent a lot of time with his wife. Rachel Revere passed away in June of 1813 at the age of 68. Paul Revere followed his wife three years later on May 10, 1818; he was 83 years old.

Sources

Paul Revere: The Midnight Rider, Dave Pryke, A&E Television Network, 1995

Friday, December 30, 2016

James Bowdoin: Post-Revolution Governor of Massachusetts

|

| Feke Painting of James Bowdoin |

Bowdoin was perhaps not as popular as the governor who served before him,–John Hancock–but that may have had something to do with his apparent absence during the American Revolution. He was suffering from what modern historians believe was tuberculosis and was involved with the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, despite his illness. When he felt better, he got right back into politics on a bigger scale. As such, he belongs among the list of Boston patriots, regardless of how undecided and sick he may have been during the war.

James Bowdoin was born in Boston to Hannah and James Bowdoin on August 7, 1726. He was technically James Bowdoin II and is currently referred to as such, though his family didn't distinguish between the two in that manner. His parents were wealthy, thanks to his father's endeavors as a merchant. Bowdoin was able to attend Boston Latin and go on to further his education at Harvard College, from which he graduated in 1745.

Three years after graduation, James Bowdoin married Elizabeth Erving. Two children came from the marriage, one of which was James Bowdoin III, who played a role in starting Bowdoin College in Maine in his father's memory.

James Bowdoin was an active, thoughtful man. He was the owner of extensive tracts of land. He dabbled in being a merchant, science, politics and maritime rescue. He was the founder of the American Academy of the Arts and Sciences, of which he was the first president. He was a member of the Massachusetts Humane Society–the name of which today is associated with animals but that focused on rescuing survivors of shipwrecks during the American Revolution. He earned an honorary doctorate from the University of Edinburgh. Clearly, he was a well thought of man in many circles.

As for political endeavors, Bowdoin was involved with the royal government in Massachusetts as a member of the governor's council from 1756 to the start of the American Revolution. He was off for a brief period when he became vocal about his shifting political views. In 1770, he wrote, "A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre" about the so-called Boston Massacre. By then, he was clearly siding with the rebels.

Whether it had anything to do with his later political leanings or not is unclear, but James Bowdoin did befriend Benjamin Franklin. It is not known precisely when they met, but Bowdoin did know Franklin at least two years before his graduation from Harvard College. The two had an interest in science in common and would send letters back and forth about Franklin's experiments with electricity.

After the American Revolution ended, James Bowdoin recovered from a long flare up of tuberculosis and ran for governor of Massachusetts. He lost to John Hancock. Five years later in 1785, John Hancock resigned for the first time and James Bowdoin became governor. It is generally thought that Bowdoin lost the first campaign by a large margin because of his seeming disdain for the lower class. When Shay's Rebellion took place, he had no sympathy for the affected "common" people. This hurt his campaign, but clearly, he was popular enough to win the second time. Therefore, it may have simply been John Hancock's popularity that killed Bowdoin's first campaign. He was in office for two years before John Hancock became governor yet again. Bowdoin passed away just three years later on November 6, 1790.

Monday, December 5, 2016

James Otis: Lawyer and Patriot

James Otis is one of the Boston men who helped stoke the fires of revolution during the 1760s. In fact, some people may say that he is the man who lit the fire. He is not as well known and he was not as prolific in his speeches and political work as many of his fellow revolutionaries. However, he was among the most intelligent and dedicated of these men. Sadly, his years of dedication and public service ended tragically.

James Otis was born on February 5, 1725 in West Barnstable, Massachusetts to James Otis Sr. and Mary Otis nee Allyne. His father was in politics. James Otis Jr. attended Harvard College. He graduated in 1743, at the age of eighteen. From there, he went to study law under Jeremiah Gridley.

James Otis' career in law began in 1748. He practiced in Plymouth, Massachusetts. However, Plymouth did not have a great need for a lawyer at the time, so two years later, James Otis took his practice into Boston. There, he earned a name for himself as a great speaker and a highly intelligent man. During the 1750s, John won a case that earned him the largest sum ever paid to a lawyer in Massachusetts until that time. His career was looking very promising.

In 1755, James Otis married Ruth Cunningham. The couple would go on to have three children together, James, Elizabeth and Mary. At the time of their marriage, they were both loyalists. That would change for James. Ruth would remain loyal to England for the remainder of her life, which, as it turns out, was longer than James' was.

James Otis shared his wife's beliefs openly until 1961. Around that time, some British revenue officers were given the authority to search the homes and places of business of Boston merchants in search of smuggled goods. James Otis decided to leave his then current position as advocate-general and represent Boston's affected merchants, for free. When the case was heard in what is now known as the Old State House, James Otis gave a roughly five-hour-long speech, addressing this issue and much more. One of his focuses was the fact that colonists had to follow Parliament's laws when the colonists were not represented in Parliament. He lost the case. However, the impact his speech had can be summed up by what future president of the United States John Adams said later. He remarked that it was on that day in the Old State House that "the child independence was born."

Soon after James Otis gave his speech at the Old State House, he was elected to the Massachusetts General Court. In 1764, he became a leader of the Massachusetts Committee of Correspondence. That same year, he wrote his famous pamphlet, "The Rights of the Colonies Vindicated." A year later, he attended the Stamp Act Congress in New York City.

In 1769, James Otis made some negative comments in the Boston Gazette that were directed at a few revenue officers. One of those customs officers and some British military men found James a few days later and mercilessly beat him. He sustained a head injury that contributed to the decline of his mental health. James Otis was able to hold on to his sanity for long enough to sue his attacker. He was rewarded a sum of money, but he would not accept it. He also received a formal apology. He remained in public office for a few more years, but by the time the American Revolution began, he was insane and in the care of his sister, Mercy Otis Warren. His life would be dotted with a few brief periods of lucidity, but he was never the same man again. He did however contribute to the American Revolution in a way that you probably will not expect.

On June 17, 1775, James Otis, then 50-years-old, decided to procure a musket and walk to Breed's Hill. That day, on Breed's Hill, a battle was raging that would become known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. James Otis showed up for the battle, fought in it, and walked home. Obviously, his hopes for the future of the country followed him in his descent into insanity.

Most of the rest of James Otis' life was spent in Andover, Massachusetts. He was there on May 23, 1783 when he was struck by lightning and killed instantly. A brilliant and at times odd life ended there. James was buried at the Granary Burying Ground in Boston, Massachusetts.

Sources

James Otis, retrieved 5/22/10, famousamericans.net/jamesotis

James Otis, retrieved 5/22/10, u-s-history.com/pages/h1204.html

Friday, November 18, 2016

Samuel Adams: The Face of a Revolution

|

| John Singleton Copley's portrait of Samuel Adams |

Samuel Adams was

one of the founding fathers of the United States, a Boston revolutionary and

the current face of Bostonian beer. He is inextricably linked with the Boston

rebels who helped ignite the revolution in the years leading up to 1775 and the

famous documents that severed the many ties between the colonies and England.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, he was not a soldier, an inventor, a

successful merchant, a tradesman or a plantation owner. His only interest and

success was in politics, but it was not for lack of trying other things.

Samuel Adams was

born in Boston on September 27, 1722. He was raised in Boston and schooled at

Boston Latin, like most of his peers. Also like his fellow Boston patriots, he

went to Harvard College, graduating with his masters in 1743. After graduation,

he became a merchant, but he was terribly bad at it. He seemed uninterested in

money, instead being interested in public service. His father was a politician,

but also a successful businessman. Samuel would not follow his father's example

in that regard.

In 1749, Samuel

Adams married Elizabeth Checkley, who bore him two surviving children before

dying in childbirth. In 1764, he married Elizabeth Wells, who cared for his

children, but had none of her own. Elizabeth Wells is remembered in a way as

the woman who put up with Samuel Adams. He made very little money in public

service. He had some land and a house, but Elizabeth did some work from home to

keep them with money while he gave speeches and attended to the masses. In

1756, he became a tax collector and actually lost money due to his ineffective

tax collecting strategies.

When Samuel

Adams' father died, Samuel also had to fight off the British over a banking

scheme his father had. It was popular among the people, but deemed illegal by the

British. Samuel Adams was on the brink of having to hand over his estate, but

he prevailed and the British were eventually run out of town anyway. Samuel

also received the run of his father's maltsing business after his death. That

was another failure for Adams.

As history shows

us, Samuel Adams was not some poor unfortunate who was just no good at

anything. The brewing discontent in the colonies gave him the perfect

opportunity to showcase his talents. When Christopher Sieder was shot, Samuel

Adams was quick to publicize the incident. Some say his speeches were such that

he was something of an agent provocateur, though on the same side as those

provoked. Indeed, the Boston Massacre occurred little more than a week after

the event. Samuel Adams was also giving speeches before the Boston Tea Party.

Suspicious? Historians think so. One thing is certain, instigator or not, he

was one of the best orators in Boston before the American Revolution.

In 1765–five

years before the Boston Massacre–Samuel Adams became a member of the

Massachusetts Assembly. As revolution became inevitable, he served on the

Massachusetts Provincial Congress and later the Continental Congress. He was

positioned politically to be one of the men instrumental in creating the new

nation. He signed the Declaration of Independence and helped draft the Articles

of the Confederation.

In 1781, Samuel

Adams retired from Congress and helped develop the Massachusetts Constitution.

Eight years later, he became Lieutenant Governor. Five years after that, he

became the Governor of Massachusetts. He remained governor until his health

dictated that he rest in 1797. He died in Boston on October 2, 1803.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)