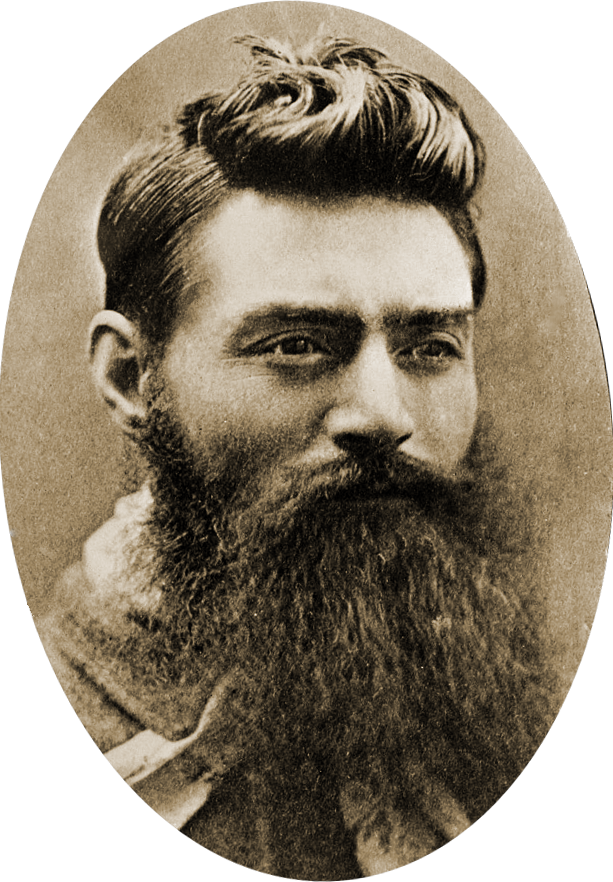

Edward (Ned)Kelly is the most infamous outlaw in Australian history. He was the leader of a

four-man revolt against the colonial police in Victoria during the 1870's. Ned

had two reputations. On one side he was a hero that stood up for the rights of

his family and friends. On the other he was a horrible villain that would stop

at nothing to get what he wanted. Either way you look at it, Ned Kelly led a

very adventurous life. The question is whether it was a life he chose or was it

a life he was forced into.

Ned Kelly was

born in Victoria, Australia in 1855. He was the first-born son of John (Red)

Kelly and Ellen Kelly. Ned’s was a humble family, and his father was not

popular with law enforcement. Red had been in some trouble before he moved to

Australia from Ireland and he wasn’t having much luck in his new home either.

He passed away when Ned was only eleven, but it seems his unlawful lifestyle

rubbed off on his eldest son.

After Red

died, Ellen was left alone with eight children to feed and clothe. She moved

the family to Eleven Mile Creek. Not long after the move, Ned and some of the

other men in his family began getting themselves into trouble. Ned was arrested

several times before he was even fifteen, but the charges were always dropped.

Ned Kelly fans believe this was because the police were persecuting him for no

apparent reason other than that he was Irish. Eventually his luck ran out and

he was sentenced to six months in prison when he was fifteen.

Less than a

year after Ned was released, he was arrested for stealing a horse. He denied

stealing the horse and told the police that he was watching it for a friend.

The friend was likely the man who stole the horse. Ned fought with the

policeman who arrested him and allegedly embarrassed the man in the street.

This probably didn’t help his case much. He was sentenced to three years in

prison. He was only sixteen at the time.

Ned Kelly

returned home from prison when he was nineteen and led a quiet life for a short

time. Soon after, his mother remarried and Ned supposedly began stealing horses

with his stepfather. This is most likely true. Many members of the Kelly family

had been arrested for stealing horses by that time. It was not an uncommon

practice then. Money was tight and relations between common people and the

government were strained.

Nearly three

years after his release, Ned was accused of shooting a police officer. The

officer, whose name was Fitzpatrick, reported that he had been at Ellen Kelly’s

house and that Ned had shot him in the hand. The only other witnesses to his

accident were the Kellys. They told authorities that Ned Kelly was not even

home at the time. They also said that the man had been hurt in an altercation

had taken place because he was being inappropriate with Ned’s sister. Neither

story has been authenticated, but Fitzpatrick was later released from the force

for being untrustworthy in an unrelated incident.

Ned was forced

into hiding with his younger brother Dan, who was also implicated in the

supposed shooting. While in hiding, Ned and Dan were joined by their two good

friends, Joe Byrne and Steve Hart. The four stayed in hiding in the Australian

bush and were rather successful at evading authorities for some time. During

this time, Mrs. Kelly had been sentenced to three years in prison for her

involvement in the Fitzpatrick incident. This lent fuel to the fire that was

Ned’s hatred of the law.

It wasn’t

until a few months later that the men had their first run in with the police.

Four policemen had set up camp near Stringybark Creek while in search of Ned’s

gang. Unbeknownst to the police, Ned Kelly and his men were camped nearby and

were aware of their presence. When two of the policemen left to patrol the area

Ned Kelly’s gang ambushed the camp. One man was shot dead and the other

surrendered. The two men who were out patrolling then returned and refused to

surrender to Ned. When they opened fire on Ned and his gang, the gang returned

fire. Both men wound up dead. During the melee, the officer that had

surrendered managed to escape and alert officials.

In November of

1878, Ned and his gang were officially outlawed and a hefty reward was offered

for each of them, dead or alive. This did not deter the group in the slightest.

The very next month, they robbed the National Bank in Euroa. In February of

1879, Ned Kelly’s gang robbed the Bank of New South Wales. This time, they were

dressed as policemen. During the second robbery, Ned gave a letter to a man

that was meant to be delivered to the authorities. In it was his side of the

story. It later became known as the Jerilderie letter.

Following the

robberies, the reward offered for the members of the Ned Kelly gang increased.

The new reward was reportedly the highest reward ever offered for a criminal in

Australia at the time. The new reward was so high in fact that one of Joe

Byrnes’ childhood friends made a deal with the police for the reward. Joe heard

of his treachery and shot him down at his front door while four policemen

cowered inside the man’s house.

Immediately

after the killing, Ned Kelly and his gang removed to a hotel in Glenrowan. They

kept around sixty hostages inside. The gang had heard of a train filled with

lawmen that was on its way to Glenrowan. They had seen to it that a length of

track was dug up so that the train would derail. The plan was to wait it out at

the hotel, but Ned had made a fatal mistake. He had allowed a schoolteacher, by

the name of Thomas Curnow, leave the hotel with his family. The man immediately

signaled the train and all was lost. The police arrived at the hotel that

evening and surrounded it.

The Ned Kelly

gang was as prepared for such an attack as they could be. They had constructed

heavy bulletproof armor and each man had his own set with some variations. This

was rather ingenious work at the time and the police were stumped by it. The

men went out into the night wearing these suits, but they were very heavy and

left their legs and arms exposed. Both Ned and Steve were shot, but neither was

seriously injured.

Dan Kelly, Joe

Byrne and Steve Hart retreated into the hotel while Ned Kelly went off into the

bush, undetected by the police. The police continued to shoot into the hotel

throughout the night. Nonetheless, many hostages were able to escape. Two

hostages were shot and killed by the police and Joe Byrne was supposedly shot

and killed while standing at the bar having a drink.

Early in the

morning, Ned came out of the bush, still wearing his formidable armor. The

police were only able to take him down by shooting him in the legs. Early that

afternoon the police set fire to the hotel. When they went into the hotel

later, they found Dan and Steve dead inside. Reports vary greatly as to the

cause of these young men’s deaths. Some say they poisoned themselves while the

hotel burned. There is no way to be sure what really happened, as there was no

official investigation.

Ned Kelly

survived the battle and was subsequently put on trial. He was tried for the

murder of Thomas Lonigan at Stringybark Creek and found guilty. His was

sentenced to hang. This sentence was carried out on November 11, 1880. Ned

Kelly was only 25 years old when he died. He may have been a criminal or he may

have been a victim. Either way, he remains a heroic symbol of hope against

tyranny to many Australians to this day.

Sources

Kelly, Edward

(Ned) (1855-1880), retrieved 7/11/09,

adb.online.edu.au/biogs/A050009b.htm?hilite=ned;kelly